On Humanizing Complicated Figures

Jay Bakker on Jimmy Swaggart

I am what I have.

I am what I do.

I am what people say about me.

I am my biggest success.

I am my biggest failure.

These, according to Henri Nouwen, are the competing and false identities that work against our true baptismal identity as the beloved of God.1

“These negative voices are so loud and so persistent,” writes Nouwen, “that it is easy to believe them. That’s the trap of self-rejection. It is the trap of being a fugitive hiding from your truest identity.”2

This trap is everywhere, and is often encouraged on social media.

Two days ago, at age 90, Jimmy Swaggart died. If you’re not as old as I am or are unfamiliar with the name, Swaggart was a massively influential pentecostal preacher and songwriter. He was also the cousin of Jerry Lee Lewis. Swaggart was famous not for rock-and-roll, but as a charismatic religious figure. Then, he became even more famous, but not in the way he wanted. He was the focus of sex scandals involving prostitutes and went from being on TV doing his televangelist thing to being the brunt of jokes on SNL. He tried to carry on with his gig but it would never be the same. He was a complicated figured, to say the least.

I used to be a minister in the Assemblies of God and am still a part of some Assemblies of God ministers Facebook pages. Swaggart was in the Assemblies of God when this all went down so naturally people had things to say. I noticed two reactions. First, there were some posts that were over-the-top with praise. Sure he had a moral failure, but look at the SOULS he reached, the impact he made, the amount of lives he touched, the size of his “crusades.” I was so saddened by this, not because nothing good can be said of a person who made a mess of their life, but because his life was being measure by the “I am what I do” and “I am my greatest success” (as they were defining success) rubric. On the other hand, people lamented his life or just didn’t say anything at all. He was either a kind of stain in our pentecostal history or just someone who needed to be erased. In this case, his life was measured by the “I am my greatest failure” rubric. I want to argue that both of these reactions — the over the top praise on the one hand, and the “can we please move on like this embarrassment never happened” on the other — are both dehumanizing. They try and make sense (or not) of a complicated man by dealing with our ideas about his persona based on what some see as the good he accomplished and others by the harm and embarrassment he brought. Neither of these are helpful responses. So what do you do when a complicated figure dies? This question is important not only for complicated public figures, but also for the funerals of complicated persons we clergy sometimes need to conduct.

Enter Jay Bakker.

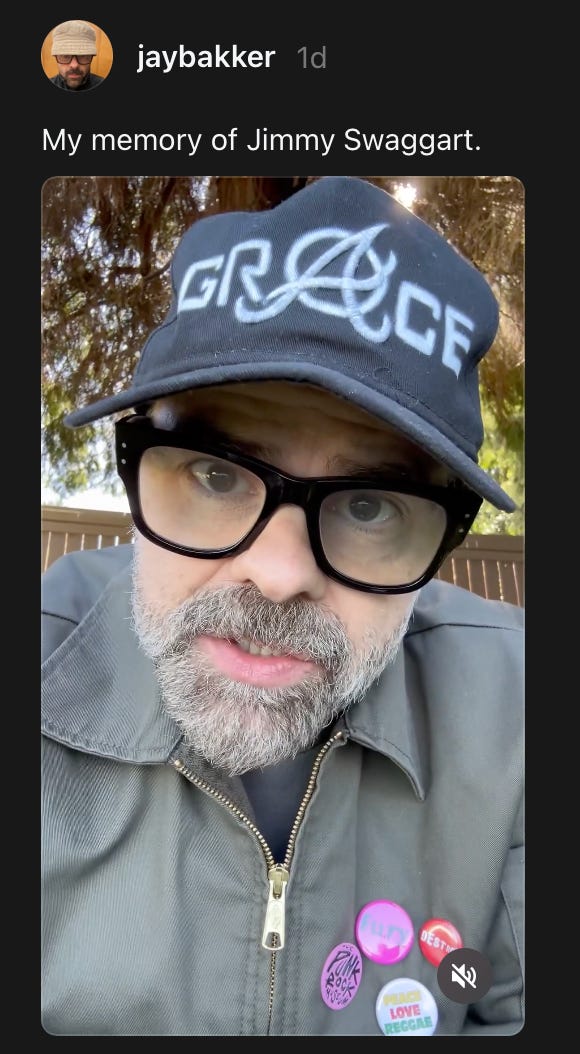

I woke up yesterday morning and saw Jay Bakker, the son of another publicly disgraced and complicated figure, Jim Bakker, post this video on Threads. (Here’s a Facebook Link for those not on Threads). Please watch it. Bakker neither dug into the best or worst moments of Swaggart’s life as the focus of his reflection. Neither did he try and uncomplicate the man. So what did Jay Bakker, a guy who is theological worlds apart from Swaggart do? He humanized him. He told a story about how Swaggart helped him when he was a 16-year-old who was trying to figure out what on earth to do to lessen his father’s pending 45-year prison sentence.

I have a son who is almost 16. He’s a kid. All 16-year-olds are. I literally can’t imagine my son having to navigate the things that Jay Bakker had to navigate as a 16-year-old-boy. But somehow, he threw a “Hail Mary,” as he put it, and called Swaggart who helped him out when literally no one — no one! — else would. Watch the video. It does absolutely nothing to un-complicate Jimmy Swaggart. What it does, though, is remind us that he was more than our ideas about him. Swaggart was an actual person. I keep saying that Swaggart was a complicated person. I’m not trying to insinuate that the rest of us aren’t. We’re certainly not all complicated in the same ways as Swaggart, but we’re a whole mess of contradictions and a mystery even to our own selves. But the truth is — and we need to spend our whole lives learning this — we are not what we do, or what we have, or what people say about us, or our best moments, or our worst moments. Really, we’re not. And neither are those people who blew up their lives. We’re flawed, broken, and complicated people who are deeply loved by God and sometimes — and usually not on TV or on stages in front of thousands of people — but sometimes, we reflect that belovedness to others when no one’s watching. Swaggart did it on the phone with an unimaginably brokenhearted 16-year-old-kid. That’s a story worth telling.

So, thanks, Jay, for showing us the way to humanize a person without having to try and un-complicate them, as if that’s our job. This is the way of love. And thanks for refusing to dance on graves.

This is the major theme of Nouwen’s work. See ch. 3 of Henri Nouwen with Michael J. Christensen and Rebecca J. Laird, Spiritual Direction: Wisdom for the Long Walk of Faith (New York: HarperOne, 2006).

ibid., 30.

Wow - I remember well all of those years, those messes. I didn’t know Jay’s story. Thanks for sharing it.

Well said. That he wore a hat with the word Grace on it was a good reminder to us as well.